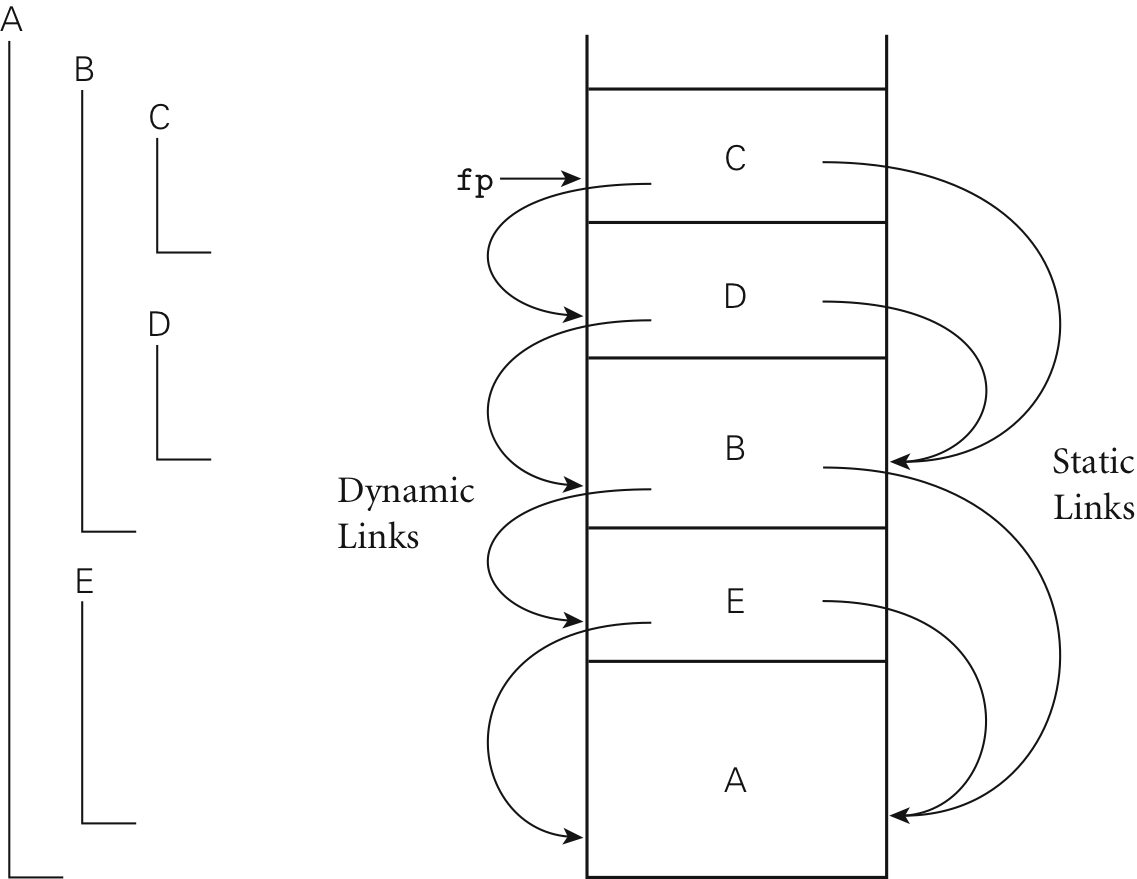

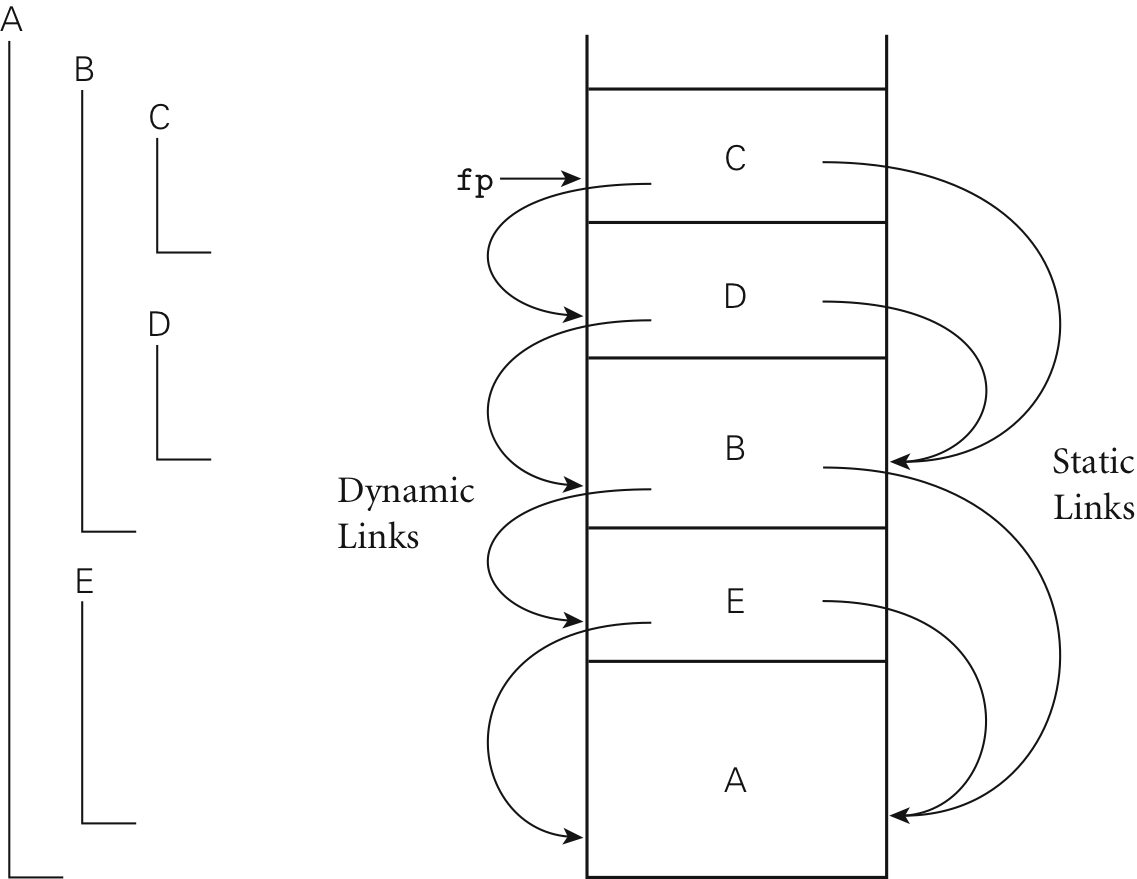

Static and dynamic links

Generally we distinguish the formal parameters (those specified in the subroutine's definition) from the actual parameters passed (though such distinctions certainly don't exist in all languages, and don't exist in assembly language programming.)

Call-by-value versus call-by-reference: in languages that have a value model, you have a bit of a dilemma when passing parameters: should you just pass the value, or should you pass a pointer to the value? If you pass the latter, it certainly makes it simple for the called subroutine to modify the underlying data. However, you quickly get quagmires associated with aliasing -- though you could remedy that by then not allowing any modifications of the state of any variable.

In functional languages, generally the value of the body of the function specifies what is returned.

In imperative languages, it's more common to have a explicit "return()"; some languages allow the function to specify its return value by either allowing an assignment to the function's name, or having some syntax to specify a special name to refer to the value of a function.

Very useful for creating containers, generics allow a programmer to specify a set of routines that can be defined over arbitrary types, and are quite analogous to macros in assembly language. Indeed, the most common implementation for generics is literally macro expansion, just as in assembly language.

Your text distinguishes the two by the level of the rewriter: pure macro expansion is done outside the language as text-rewriting (for example, m4 could be used to do this), but generic expansion is done by the compilation environment, giving it an ability to make syntactic and semantic distinctions that m4 could not.

Exceptions are unexpected/unusual situations that are not easily handled locally. Run-time errors, particularly those related to I/O, are often awkward at the point of contact, and often are more cleanly handled elsewhere. If the elsewhere is up the stack in a parent activation record, then the stack needs to be unwound to that point.

Unwinding means not only popping off all those activation frames, but also restoring the state at the point of recovery in the propagation process.

These are pretty rare; I don't remember ever seeing these actually used anywhere (well, that is outside of assembly language; co-routines are trivial in assembly language), though apparently some languages do like to use these to implement iterators.

As your text notes, threads are quite similar in many ways, and offer more functionality at a very modest price.